Muni Market Q&A: Bond Yields on the Rise

Since the Great Recession in 2008–2009, Treasury yields have hovered at or near historic lows for the past decade. But lately, yields have shown signs of life, with 10-year Treasury yields increasing 100 basis points (or 1%) since last August. Is this temporary or a significant, long-lasting trend? And if rates are going up, how high – and how fast – will they go? We asked Strategas’ Head of Fixed Income Research Tom Tzitzouris to read the bond-market tea leaves and share his perspective on what issuers and investors can expect going forward.

It looks like bond yields have started to climb higher than most economists were forecasting even last quarter. Are you expecting rates to keep increasing, or is this a temporary move like we saw in 2018?

I think the short answer is “both.” I do think we're oversold in the five- to 20-year part of the yield curve, which is to say that these bonds are selling for a bit less than their fair value. (As a reminder, when bond prices go down, bond yields go up, which is what we’re seeing now.) To put some numbers behind that, I would say anything above 1.50% right now on the 10-year yield is probably a buying opportunity for investors.

So with bonds this cheap, we’d normally expect overseas investors to find a lot of value here and pick up the slack, which would push prices back up and yields back down. But what we’re seeing is these investors only dipping their toes in the water. They’re looking at the headlines and considering the possibility of additional stimulus this summer or potential Federal Reserve action that could further devalue the dollar, and they’re being cautious. So we could very well remain oversold at these levels until the economy catches up to where headlines and expectations say they should be.

That said, when I said “both” earlier, it’s because we think yields are still going higher between now and the end of the year. We're at 1.60% on the 10-year, and our forecast is to be at 1.90% by year-end, if not higher. So long as headlines continue to be supportive and until there's some sort of weakness on the U.S. economic front, we think yields will keep going up.

What causes rates to rise generally? Is that what’s at play now?

So the order of operations may be a little different for each cycle. Sometimes the Fed jumps the gun and gets a little ahead of where it should be in terms of tightening, and yields start rising faster than they should. That happened a lot in the past decade, where real yields were rising a little too soon and a little too fast, and you could tell right away it wasn't going to be sustainable. But what's happening this time is a more typical cyclical expansion. You're getting a cyclical recovery – driven in part by housing, driven in part by government stimulus, driven in part by a reopening of the economy – and that naturally pushes yields up.

It’s worth talking more about the current housing boom. You’ll remember that the housing market was devastated by the recession in 2008–2009. In the years following, though, housing never fully reopened – and without housing, you don't get the cyclical expansion and drivers in the low-skilled labor sectors, particularly retail, construction and materials. When housing starts to boom, you get a real re-opening of the economy, which translates into rising inflation expectations. And as inflation expectations rise, so do real yields.

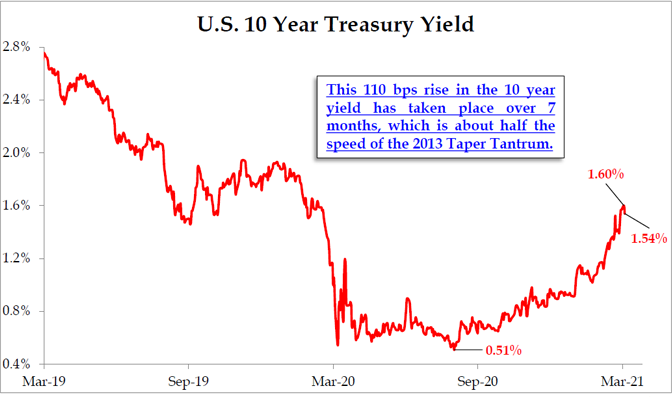

In a recent Strategas article, you mentioned that the rise in rates is much slower compared to 2013’s “taper tantrum.” Why is that, and why is that important?

Source: Strategas Fixed Income Strategy Report, March 9, 2021.

It’s slow because when you account for inflation, real rates really haven’t risen all that much. Since last August, they've risen about 40 basis points, a far cry from the 110 basis points for 10-year Treasury yields over that time. In contrast, during the taper tantrum in 2013, you saw real interest rates drastically rise – from late April to late June in 2013, they were up about 130 basis points. So by comparison it’s been pretty slow.

Why that’s important is that real yields are now beginning to catch up and inflation is being talked about again. I mean, for investors, the fear shouldn’t be that we've got a 10-year yield at 1.60% and real yields have moved a little bit. The fear should be that our real yields could jump 100 basis points from here – and still be relatively low. If the economy is going to heat up to a 10% GDP for two straight quarters, inflation becomes a real concern. If I’m a bond investor, I'm going to tread cautiously.

You mentioned we could reach 1.9% on 10-year Treasury yields by the end of the year. How much higher could it go? Is 4% or higher a possibility?

I do believe we're on the way there this time. And it goes back to a couple of the reasons I pointed out earlier. You have housing contributing this cycle, and that itself is a big driver of interest rates, as is low-skilled labor finding their way back into the workforce. You also have the aggregate demand backlog to support the reopening of the economy. Even before you look at the federal stimulus coming from Washington, this cycle is going to look a lot more like a typical reopening of the economy, and with that, you should expect to see rates move higher and sooner on the long end of the curve than we saw last cycle.

Now, does that get you to 4%? By itself, probably not – it probably only gets you back up to roughly the levels we hit the last cycle, maybe 3.50% on 10-year yields, and instead of having that happen eight years into the cycle, you might reach it three or four years into the cycle.

But if you add in fiscal stimulus, the picture changes a little bit. What does the Fed do? Because if the Fed monetizes that fiscal stimulus, then it's supplementing the aggregate demand. So you have to raise your expectations: Instead of 3.50%, now you have to go above 4.00%, because you probably are seeing economic growth close to 6% and inflation running at about 3%.

So I expect the 10-year Treasury to come pretty close to, if not exceed, 2% by the end of the year. By the end of 2022, we could come close to 3%, and by 2023 or early 2024, we could be looking at a 10-year Treasury that's at or above 4%. And what’s interesting is even with this path I've laid out, that would not be particularly fast for any cycle. That's still a somewhat leisurely pace of yield increases.